Here is an overview of the individual chapters:

Part 01 - "Dream job" concert photographer?

Part 02 - Legal issues

Part 03 - Special features of concert photography

Part 04 - Behavior in the "trench"

Part 05 - The right equipment for concert photographers

Part 06 - Tips and tricks from (concert photography) professionals

Part 07 - Image composition (Part 1)

Part 08 - Image composition (Part 2)

Part 09 - Recommended camera settings

Part 10 - Post-processing

Figure 2-1: As an experienced photographer, you are always amazed at the "courage" of many concertgoers who take photos (and videos) of the concert with their cell phone cameras - without permission. And - what is even worse from a legal point of view - they also distribute them indiscriminately on facebook, Youtube and other internet platforms ... Nikon D800 with 2.8/70-200mm Nikkor with a focal length of 170mm. 1/200 second, Blender 4.5, ISO 800.

(Photo © 2013: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Experienced concert photographers can "tell you a thing or two" about how difficult it often is to negotiate with concert promoters, who in turn are in negotiations with the artists - or their management. Concert promoters therefore regularly only pass on the restrictions imposed on them by the artists. They often do not have much leeway.

Figure 2-2: Kylie Minogue in concert on the Aphrodite-Les Folies Tour 2011 on March 1, 2011 in Berlin. According to insiders, this singer, or rather her management, is one of the "most difficult" negotiating partners when it comes to granting photo permission (and the subsequent publication of the photos). The rule of thumb is (with a few laudable exceptions such as U2, Scorpions, Westernhagen and others): the better known the artist, the more difficult the negotiations about photo permission and the publication of the photos. If a star (or their management) doesn't like the idea of professional photographers taking photos at a concert, the photos are sometimes stopped without further ado.

An "in-house" photographer is then used, who can then offer photos of the concert exclusively - of course after consultation with the management (who can sort out the displeasing photos beforehand by means of a veto right). Canon EOS-1D Mark IV with EF 2.8/400mm L IS USM. 1/250 second, Blender 2.8, ISO 1000.

(Photo © 2011: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

"A special form of gagging, however, is that the images may only be given to one medium, i.e. a newspaper, are to be removed from the archive after a certain period of time and/or are to be submitted to management for approval before publication. Censorship." (Concert photographer Sven Darmer, in the photo textbook "Konzertfotografie" by Brüggemann, Becher, Meister, Darmer, Lippert; mitp Verlag, 1st edition 2012).

But why can the artists - via the detour of the concert organizers - unilaterally enforce their demands so strongly against the photographers? After all, there is freedom of the press, which should enable uncensored reporting. In order to understand the legal side of this constellation, which is unfavorable for photographers (artists or their management negotiate the concert appearance with the concert promoter, who then, as a negotiating partner with the photographers, determines the conditions under which photographs can be taken), it is necessary to understand the effects of the "right of the person depicted to their own image" and "domiciliary rights", which is why both are explained in more detail below.

Figure 2-3: Robbie Williams (here at the free concert on October 23, 2009 in Berlin) has since abolished the gagging contracts since he has been together with his girlfriend/wife Aida Fields. A few years ago, however, recordings like this were still a rarity, as it was difficult to get accreditation.

(Photo © 2009: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

2.1 The right of the person depicted to their own image

How would you feel if one day, while shopping at the supermarket checkout, you discovered a pack of cigarettes bearing your likeness? And underneath it says (in quotation marks to simulate an original quote from the person in the picture, i.e. you): "I love smoking XYZ cigarettes for my life! Only these give me self-confidence and make me happy!" Would you be thrilled? Or would you feel exploited? After all, you weren't asked if you wanted to do advertising for a cigarette brand; and you didn't get paid either ...

And what if you are a convinced non-smoker because you believe - and it has been scientifically proven - that cigarettes are responsible for the deaths of millions of people? What would be your first spontaneous thoughts if you saw your face on one of these deadly cigarette packs?

"That's not possible! They can't just do that! Without asking me! Well, they'll hear from my lawyer!" I'm sure your first reaction would be something like this. And your lawyer will also confirm that you have a good chance of suing the cigarette industry for injunctive relief and damages, because the "right of the person depicted to their own image" states that everyone should be able to decide for themselves whether images of them are published at all and in what context.

§ Section 22 KunstUrhG

"Portraits may only be distributed and publicly displayed with the consent of the person depicted. Consent shall be deemed to have been granted if the person depicted has received remuneration for allowing himself to be depicted. (...)"

In the case we have just mentioned, your portrait on the pack of cigarettes, this means that You were neither asked nor paid for the cigarette industry to advertise with your likeness, which is why the chances of a successful lawsuit are very good for you, should it not come to an out-of-court settlement.

But back to concert photography. The question now arises as to whether there are exceptions to this paragraph that make the publication of concert photos possible after all, even without the express permission of the artists depicted (and the concert organizers, see 2.2 The organizer's domiciliary rights).

First of all, it should be checked whether concert photos may be published if admission has been paid (and the artist(s) have received a fee for their performance). After all, Section 22 KunstUrhG states: "Consent is deemed to have been granted if the person depicted received remuneration for being depicted."

However, the fee is not to be regarded as remuneration for the fact that the artist or artists were photographed, but as remuneration for the fact that he or they performed music. No photographer will get away with claiming in court that allowing the artists to be photographed is part of their duties if they receive a fee for their performance.

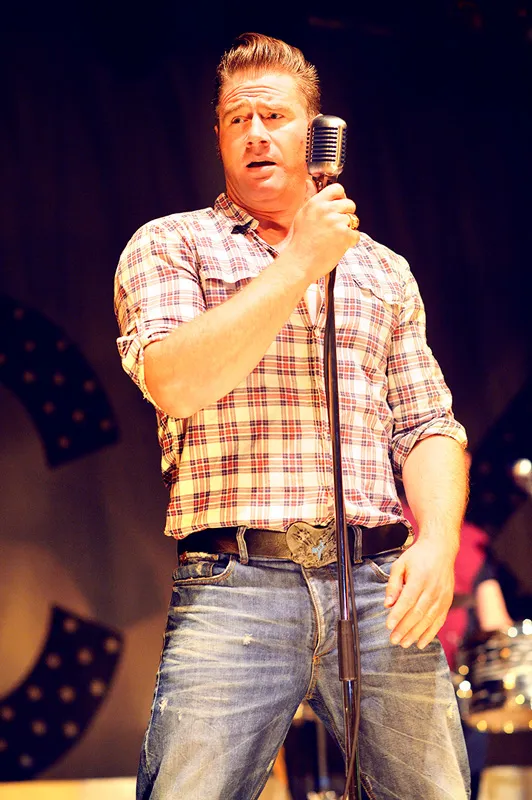

Figure 2-4: Dick Brave (aka Sasha) receives his fee for his performances for entertaining the audience musically. It is not a photo fee, i.e. no payment for allowing himself to be photographed by the concertgoers and photographers and approving the publication of the photos in any form. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85mm Nikkor. 1/200 second, Blender 2.5, ISO 2500. The photo was taken at the acclaimed concert at the Ruhr Tent Festival on August 26, 2012.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

But are there perhaps other exceptions that allow the concert photos to be published after all? § Section 23 KunstUrhG ("Gesetz betreffend das Urheberrecht an Werken der bildenden Künste und der Photographie") lists exceptions to the general ban:

§ 23 KunstUrhG

"(1) The following may be distributed and displayed without the consent required under § 22:

- Portraits from the field of contemporary history";

- Images in which the persons appear only as an accessory next to a landscape or other location;

- Pictures of meetings, processions and similar events in which the persons depicted have taken part;

- portraits that are not made to order, but where the dissemination and display serves a higher interest of art."

- Ad 1: Concerts are regularly classified by case law as historical events that may be reported on without special permission. Provided that no other rights of the persons depicted or third parties are violated, which is regularly the case at concerts, with a few exceptions of "free and open-air concerts" (see 2.2 The organizer's domiciliary rights.) In addition, reporting on a concert event is to be classified differently than if the likeness of a musician, taken at a concert, is used for other commercial purposes such as advertising for a specific product. While musicians have to put up with the reporting, this does not apply to the misappropriation of portraits for advertising purposes.

- Ad 2: Concert photos in which the musicians are only depicted very small on the huge stage for creative reasons will probably not be considered freely publishable even then, because even in such photos - regardless of the particular image design - the musician or musicians are not to be classified as "accessories" in addition to "other locations". The term "accessory" is therefore not only to be interpreted depending on the size, but above all on the significance in relation to the image statement. DJ Bobo may look very small on a large concert stage, but he is certainly important for a photo showing one of his concert excerpts and is therefore not just to be classified as an "accessory".

- ad 3: When a musician gives a concert, is he participating in an "assembly", an "elevator" or a "similar event" in the legal sense of §23 para. 1 sentence 3 KunstUrhG? The question must be answered in the negative here; the legislator meant demonstrations, marches by political parties, etc. If a musician gives a concert, this is not one of the exceptions under Section 23 (1) sentence 3 KunstUrhG that would justify the publication of photos of this without the consent of the artist.

- ad 4: Whether normal concert photos serve "a higher interest of art" may also be doubted. At the very least, this exception is not a carte blanche for photographers who think they can invoke it if they want to distribute/publish concert photos.

Figure 2-5: No one - not even persons in the public interest - need fear that third parties can proceed at will with photographs or video recordings in which the person in question can be recognized. In particular, these cannot be used for merchandising purposes without the consent of the person depicted. However, the situation is different for editorial reporting: Persons of public interest (politicians, musicians, important business leaders of large companies, people from high society, etc.) must accept it if they or their actions (as long as these are not too private or intimate in nature) are reported in the press.

But does this also apply to normal concert photos? The photo shows Tim Bendzko at a concert on August 24, 2012 at the Zeltfestival Ruhr. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85mm Nikkor. 1/500 second, Blender 2.8, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Now, of course, the question arises as to what extent "the right of the person depicted to their own image" applies if the person is no longer individually recognizable? In the age of image processing, it is relatively easy to distort faces in such a way that one's own parents would no longer recognize their daughter or son. In this case, the photographer could waive the need to obtain permission to publish the images.

However, it should be noted that recognizability can also result from "accompanying circumstances": "If a person can be clearly identified by the context, they can object to the publication, even if their facial features are not shown at all." (Frankfurt Higher Regional Court, judgment of 23.12.2008, ref. 11 U 21/08)

It may therefore not even be important whether the person is clearly recognizable, but also whether they are nevertheless identifiable on the basis of other circumstances (e.g. the context shown, etc.). Even then, permission from the person depicted is required to publish the photos.

Figure 2-6: The person depicted is not individually recognizable, and the context does not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to which concert this might be. I deliberately photographed this motif as a sort of silhouette against the light, as I did not have permission to photograph it. However, it can still be used in such an "abstract" way, and it is also atmospheric. Nikon D3S with 4/24-120mm Nikkor at a focal length of 120mm. 1/200 second, Blender 4, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Conclusion on the subject

The right of the person depicted to their own image as a special form of the general right of personality is to be understood as protection of the individual, so that no one can distribute/publish their likeness at will. Images may not simply be used for advertising and merchandising purposes in particular. To ensure that this right does not undermine the freedom of the press, the legislator has created exceptions (see Section 23 (1) KunstUrhG) that allow press photographers to publish photos that are of particular historical significance, for example, without the consent of the person depicted. Recent case law uses a graduated protection concept: In each individual case, after weighing and balancing interests, it must be examined whether the photograph of the person in question is of historical significance and may be published accordingly - for the purpose of reporting.

The following applies: the more a person is in the public interest, the more likely it is that photos depicting this person can be used for reporting purposes - even without the consent of the person depicted.

In the practice of concert photography, however, there is another legal construct that makes it possible to photograph and publish the results through negotiations as an option. These negotiations take place between the musician and the concert organizer on the one hand and between the concert organizer and the photographer on the other. This is made possible by the concert organizer's "domiciliary right", which we would like to take a closer look at below due to its outstanding practical relevance in the field of concert photography.

2.2 The organizer's domiciliary rights

Imagine you are hosting a party at your home. All the friends and acquaintances you have invited are coming to this party. You can, but do not have to, let strangers into your home; you also have the right, of course, to expel disagreeable guests (who, for example, start a fight among the guests while drunk or break your best furniture) from your home. You can decide what music is played, whether the TV should be switched on and whether guests are allowed to kick over the freshly planted flowers in the front garden. In short: you have the domiciliary rights and the guests must follow your instructions! If they don't like it, they can leave or even be involuntarily expelled (with the help of the police if necessary).

And it's similar in the music business, where the concert organizer - in consultation with the performing artists - decides what photographers are allowed to do (if they are allowed at all) and what not. The rule of thumb here is that the more popular the current artists are, the stronger their negotiating position vis-à-vis the promoter. This means that very well-known artists can impose their demands almost at will - and the organizer will say "yes" to anything to enable the musician(s) to perform at all.

Figure 2-7: These concert photographers were all "accredited". They had permission from the organizer to take photos during the concert and also to publish the photos. In the run-up to the concert, there were agreements between the organizer (the "host") and the performing singer (here: Jan Delay) as to whether photographs may be taken, how long, when and to what extent the photos taken may be published. The last point in particular, the commercial use of the photos taken by granting a license (as a rule, it is not the "physical" photo that is sold, but the license to publish it, for example in magazines, on websites, etc.) interferes with the aforementioned domiciliary rights of the concert organizer. Therefore, you should never - just because you were not discovered taking photos during a concert - publish or pass on the photos you took, unless you have the organizer's express written permission to do so. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70mm Nikkor with 24mm focal length used. 1/160 second, Blender 3.5, ISO 5000.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Conclusion

"The organizer of a concert has all the rights associated with it. This includes in particular the domiciliary right. He may therefore prohibit photographers from taking and selling photos of the event or of the performing artists. The same applies to other closed events, such as sporting events." (From the textbook: "Fotografie und Recht", Kötz/Brüggemann, mitp-Verlag, April 2009, 34.95 euros, approx. 200 pages)

Figure 2-8: If Mick Jagger (who has been in the music business for 52 years!) gives a concert with his Rolling Stones, the organizers will not insist on enforcing their conditions if this would jeopardize the band's performance. The photo shows Mick Jagger at the Rolling Stones concertin Berlin's Olympiastadion on June 15, 2003. In the meantime (2014), the Rolling Stones have been on stage for over half a century. There have always been rumors about the band's breakup - internal disputes, mostly between Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, were regularly put forward - throughout the Stones' history. They probably also ensured that the concerts were regularly sold out - out of concern on the part of potential concert-goers that a break-up of the band was really imminent and it would be the last opportunity to see the Stones live. But this was probably just part of the Stones' ingenious marketing, as they had already artificially built up their own image as the "bad boys of rock 'n roll" in the sixties (although they actually came from good, middle-class backgrounds). (Photo © 2003: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

As we have just explained, it is important to note that house rules apply to closed events. This means that the event does not necessarily have to take place in a "house" for domiciliary rights to apply. Open-air events that are "closed" by a fence, for example, so that not everyone can freely enter the festival grounds, are also covered by domiciliary rights. At many music festivals in the summer months in particular, the grounds on which the events take place are surrounded by a fence or a wooden wall. The primary purpose of this, of course, is to set up one or more cash desks at the entrances and to charge festival visitors admission. The fact that the organizer simultaneously acquires domiciliary rights is a pleasant side effect for him. The decisive factor, however, is free access, which is no longer a given at most festivals due to the barrier measures.

However, there are also music festivals that deliberately do without barriers in order to give everyone the opportunity to attend the event for free. These "Umsonst-und-draußen-Festivals" are usually organized with a lot of passion and supported by the city for cultural reasons. These events would be inconceivable without the sponsors, who use the events for advertising purposes in order to create a positive brand image among the respective target group.

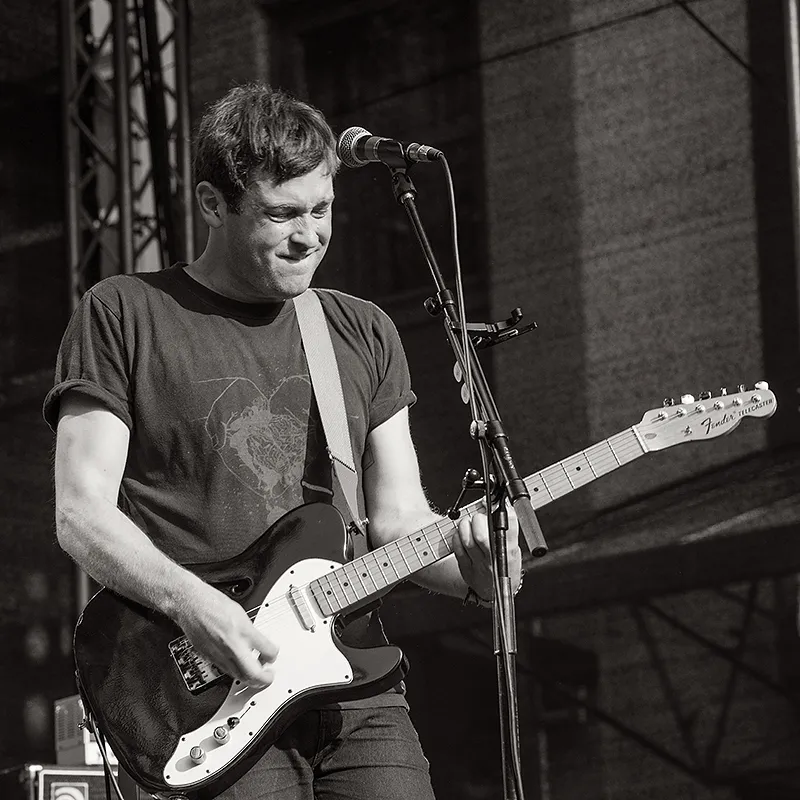

Figure 2-9: Bochum Total is one such successful (and long-established) music festival that takes place every summer in Bochum's city center and is open to the public. This year, around one million visitors are expected to attend the free event. Photographers can also shoot concert photos from the crowd (the locations are usually no worse than in the press pit, which is only open to accredited photographers) without having to worry about accreditation beforehand. (Tip: secure one of the front seats in good time; it's best to arrive at least half an hour before the concert starts). This photo of the guitarist from Apologies, I Have None, was taken at Bochum Total in July 2013. I was standing in the front row between the other concertgoers, as I had decided to take a few photos here at very short notice, meaning that accreditation was no longer possible.

In contrast to my colleagues in the press pit, I had less arm room, but I had the advantage over them that I didn't have as much of a "from below" perspective due to the slightly greater distance to the stage. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85mm Nikkor. 1/1600 second, Blender 2, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2013: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

2.3 The freedom of panorama

Many photographers think they can invoke the freedom of panorama when photographing outdoor concerts. But this is wrong, as a glance at the Copyright Act shows:

§ Section 59 UrhG - Works in public places

"(1) It is permitted to reproduce, distribute and publicly reproduce works that are permanently located on public paths, streets or squares by means of painting or graphics, by photograph or by film. In the case of buildings, these rights only extend to the external view."

The two criteria "permanent" and "public" are decisive. Although a "free and open-air festival" is by definition "public", it is never "permanent", as it is only temporarily in the public domain. At the end of the festival, the stages are dismantled, along with the lighting and event technology and the musical instruments. However, photographs of exterior views of buildings are covered by the freedom of panorama in Section 59 UrhG, provided they were taken from a public path, street or square. The same applies to other works protected by copyright, such as sculptures, installations, etc. Temporary art events (such as music festivals), on the other hand, are not permanent works within the meaning of Section 59 UrhG.

2.4 Do (concert) photographers also have rights?

Yes, of course they do!

Copyright protection

"Copyright protection arises with the creation of a photograph itself, so it does not have to be applied for. Every author has the right to be mentioned by name (or otherwise, for example the internet domain) when a photograph is published, and this also applies to advertisements, which is an advertising tool for us photographers that should not be underestimated. Copyright protection for photographic works remains in force for a period of 70 years after the death of the author, for photographs it is 50 years." (from the textbook: "Fotografie und Recht", Kötz/Brüggemann, mitp-Verlag, April 2009, 34.95 euros, approx. 200 pages). Our photos are protected by copyright. It is irrelevant whether the photos are particularly artistically designed or simply taken as a snapshot ("snapped"). This distinction between "photographic images" and "photographic works" is only relevant when it comes to the term of protection of the images: Copyright protection for photographic works remains in force for 70 years after the death of the author, whereas for photographic images it is 50 years.

Figure 2-10: Good to know: This photo from the Wir sind Helden concertis also protected by copyright. I did not have to apply for this protection, but it was created at the time I pressed the shutter release (i.e. at the time the photo was taken, i.e. at the same time). Nikon D3S with 1.4/85mm Nikkor. 1/250 second, Blender 3.5, ISO 2000.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

For concert photography, however, the decisive factor is what was negotiated between the respective parties. In other words: If we (for example, due to a poor negotiating position) go along with every gagging contract of the concert organizers, we don't need to complain that we have ceded all of our artistic and economic freedoms.

Of course, as an individual photographer you are hardly in a position to always enforce your wishes. The rule is best described as "eat or die!". In other words: We photographers have to follow the terms of the concert organizers - or we refrain from reporting by means of photography.

And this is precisely the starting point that makes our position look not so bad: If we can also convince our other colleagues from the press that we will all - without "strikebreakers" breaking ranks - boycott concert events where accreditation is only possible by entering into gagging contracts, then musicians and concert promoters will also realize at some point that they are dependent on the good work of (press) photographers. After all, beautiful photos of a concert are always great - and above all free - advertising for it.

No concert photographer should accept the following conditions (which have actually been imposed in the past) ("gagging contract"):

- Veto right of the organizer or the musicians regarding the publication of photographs of the concert: this restriction means censorship! Don't let the power of decision be taken out of your hands when it comes to deciding which photos you can publish!

- Shortening the photography time to 10 seconds of the first 3 songs. This is pure harassment and means that you are under enormous stress, because who can deliver artistically valuable results in 30 seconds? An outstanding photo would be pure chance - but no longer the result of skill.

- Prescribed shooting angles: Don't let non-photographers limit you when it comes to composition! Instead, argue that you need your artistic freedom to deliver good results.

- Prescribed image editing (for example, slimming down the artists): While image manipulation is (unfortunately!) not uncommon these days, it is not (yet) necessarily common in photojournalism, which includes concert photography (see Tutorial 10: The post-processing). In this respect, refuse if the artist wants to be retouched or slimmed down out of vanity. Especially as such elaborate image editing costs you unnecessary time (and therefore money).

Final conclusion

In no other area of photography are there as many restrictions for photographers as in concert photography. But don't put up with everything! Even if the individual photographer is in a poor negotiating position with concert organizers and musicians (or their management), they should not blindly sign every agreement presented to them. At the latest when contractual conditions lead to the artistic or commercial freedom of the photographer being significantly curtailed, it makes more sense to refrain from photo coverage altogether! If the photographers are in agreement with each other, organizers, musicians and managers will quickly realize that they are not dependent on a single photographer, but also that they cannot do without the services and skills of the photographers in general.

Figure 2-11: If atmospheric photos of concerts no longer appear in the press, an important advertising effect for the musicians is lost. They benefit from the fact that they and their (successful) concerts are reported on free of charge. It is precisely the photos that encourage newspaper and magazine readers to attend a concert of their favorite band again.

In this respect, we concert photographers are not only supplicants to the musicians and concert organizers, but also professional artists who make a not inconsiderable contribution with their photos so that concerts can take place in the masses in the first place. Jan Delay with band at the Ruhr Tent Festival in August 2010. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70mm Nikkor with a focal length of 55mm. 1/2000 second, Blender 5.6, ISO 3,200.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

2.5 License fees: Calculation and negotiation

If you want to sell your (concert) photos, you will naturally think about how much you can get per photo. Beginners in particular find it very difficult to determine the selling price.

The following usage rights concept should help you to get a feel for what a "reasonable" price is.

As a rule, professional concert photographers no longer sell "physical" photos ("prints"), but rights of use. Even if, in exceptional cases, physically existing photos are still passed on for this purpose (the normal case in the Internet age is now the passing on of digital photos), the sales price is not based on the value of the photo print, but on the extent to which the customer wishes to use the photo(s).

A distinction is made between material, spatial and temporal use.

Material use:

The decisive factor here is what the photos are used (utilized) for. The greater the number of types of use envisaged by the image user, the greater the scope. Examples are Use of the photos in a daily newspaper for reporting, for a magazine to illustrate the article about the band's history, for a CD cover of the band's latest CD, for a poster of the band, as a promotional flyer for the next concert tour, etc. It becomes clear that the more types of use are envisaged, the higher the fee the photographer should receive for the photos.

Spatial use:

The scope of spatial use is about where (geographically speaking) the photos are to appear everywhere. It makes a difference whether the photos only appear in the local section of a Bochum daily newspaper or in a Germany-wide magazine or even Europe-wide or worldwide. The larger the geographical area in which the photos are published, the higher the photographer's fee should be.

Temporal use:

If you are selling a photo for a poster that references the upcoming tour of the band pictured, then the longer the posters hang (the longer the tour lasts), the higher your fee should be. It's easy to see that photos on a poster that only advertises a band's upcoming concerts for two weeks will earn you less than if the poster hangs on advertising pillars etc. for months. The principle applies: the longer the period of use, the higher the revenue for making the photo(s) available.

This usage rights concept says nothing about the actual amount of the image fee; it merely serves to differentiate when different uses (in terms of subject matter, space or time) of photos are planned.

It should not be forgotten that image fees are not "fixed" anywhere - but are the result of negotiations between the image rights provider (us photographers) and the user (the user of the photos). The fact that the flood of digital images has caused sales revenues for the granting of usage rights to photos to fall significantly is proof of this. The granting of rights of use for photos (the "sales revenue") is also subject to the market economy laws of supply and demand.

Anyone still expecting "concrete prices" for the allocation of their photo usage rights at this point should refer to the publication "Bildhonorare 2014" by the MFM (Mittelstandsgemeinschaft Foto-Marketing) of the BVPA (Bundesverband der Pressebild-Agenturen und Bildarchive e.V.): "The annually revised and updated image fees of the Mittelstandsgemeinschaft Foto-Marketing (MFM) have been available as a print version since February. The overview of standard market remuneration for image usage rights serves as a basis for calculation and negotiation for market participants - both image providers and image buyers." (Source: http://www.bvpa.org/news/1026-mfm-bildhonorare-2014)

These fee recommendations are not to be seen as a fixed figure in the negotiation poker for "appropriate" prices for photo usage, but rather as an approximate guideline in the context of price negotiations between providers and buyers. Incidentally, they are also regularly used by the German courts as an indication of how photo uses can be priced.

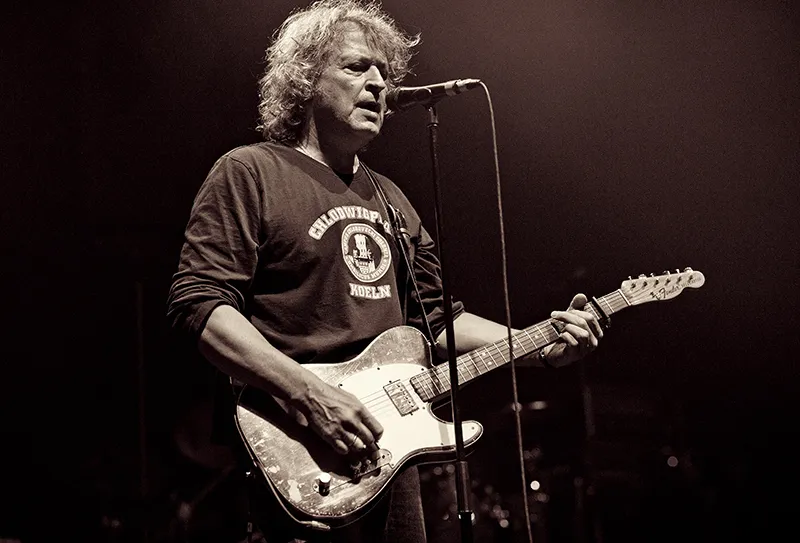

Figure 2-12: How much could I charge for this photo of Wolfgang Niedecken, frontman of the band BAP? Well, it depends on what the photo is to be used for (a CD cover earns a higher fee than publication in a daily newspaper reporting on yesterday's concert), how long the photo will be published for (for example, it makes a big difference whether the photo is only to be used for one day, e.g. daily newspaper, or for 20 years or longer, e.g. CD cover) and how wide the geographical distribution of the photo is (will it only be published in Cologne or even worldwide?). The fee recommendations "Bildhonorare 2014" of the MFM of the BVPA provide a valuable orientation aid in the negotiation poker with the image user. Nikon D3S with 1.4/85mm Nikkor. 1/400 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 1250.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)