The special features of concert photography are:

- Legal restrictions: Others (concert organizers, musicians and their managers) determine what may be photographed, when and how, and the extent of possible uses (publication of the photos).

- Two very enjoyable hobbies (music and photography) merge into concert photography, which has increased its popularity enormously.

- Hardly any active creative possibilities for concert photographers.

- Largely predetermined perspectives, depending on the design of the concert hall/stage and the accreditation status.

- Uninfluenceable, rapidly changing lighting situations make exposure control difficult for photographers.

- Own light (e.g. system flash) must not be used.

- Often extremely short time frames for taking photos (usually only three songs long; sometimes even shorter), which means that the photographers work under enormous stress, but at the same time - as with hunters or paparazzi - the adrenaline level skyrockets.

Figure 3.1: With the courage of despair: concert photographers don't have many creative options, have no influence on the (often difficult) lighting and usually only have three songs to get the shots they need. All this means stress, and then you sometimes "bravely" take pictures in full backlight ... Jan Delay in concert at the Ruhr Tent Festival, August 20, 2010. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70mm Nikkor, with focal length 24mm. 1/2000 second, Blender 3.5, ISO 1600.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Hardly any active creative possibilities available

Especially for me as an advertising photographer, who is used to doing everything possible to plan the photo result precisely and independently of chance and to influence it in the sense of the image idea (according to my own specifications or those of the client), concert photography with its many imponderables is not only a great challenge, but above all also a change from my daily (controlled) work as an advertising photographer.

As a concert photographer I can NOT:

- ... shout to the artist on stage (give stage directions) on how he/she should best pose for me; I cannot give tips on which pose or which angle to the light looks more advantageous.

- ... design the lighting or stage set-up according to my ideas.

- ... have any poses or movements of the musicians repeated, for example to shoot variations.

- ... influence the color scheme of the clothing in harmony with the stage set-up and lighting.

- ... banish distracting elements (such as microphone stands or water bottles or speakers at the feet of the actors) from the stage.

- ... change my shooting position at will.

- etc.

Figure 3.2: Of course, I would have loved to shout to the guys from Culcha Candela (concert on August 20, 2011): "OK, and now please line up in my direction again and wave at me!" ... But the knowledge of how the security would react to such attempts at interference made me prefer to keep quiet and so I simply took the photo from the side, which may not have been ideal, but at that moment there was no other option. Nikon D3S with 4/24-120mm Nikkor, using a focal length of 78mm. 1/160 second, Blender 4.0, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Although it is quite difficult for a concert photographer to impose his own style of photography because there is hardly any opportunity to intervene actively and creatively, it is precisely this circumstance that gives this type of photography its appeal: the photographer becomes the hunted (due to the limited time available) and yet is also the hunter: always on the lookout, eager for the perfect moment in which light, pose and camera technique come together in an ideal way; ready to take the brilliant shot when the opportunity presents itself.

In this respect, concert photography is perhaps also a bit "back to the roots". Even though fast lenses and modern cameras with low noise and high ISO values are generally used, the material battle that takes place in other areas of photography is not possible in concert photography (because it is not permitted by the organizers).

In addition to high-quality equipment and mastery of the (camera) technology, what counts is good preparation (if you know the musicians' songs, you know when to use which instrument and when to expect solos or effective show interludes), quick reactions (for example, when new, unpredictable things happen in the choreography or a musician gets particularly active), a feel for the right equipment (because it often matters which lens is attached to the camera, as a lot of time is lost unnecessarily when changing lenses), artistic image composition based on instinct (anyone who thinks about image composition rules while taking pictures has already lost!) and - last but not least - an understanding of photographically relevant relationships (for example, of time, aperture and ISO value in order to be able to set the desired combination of parameters quickly and independently of the camera's automatic exposure control).

Figure 3.3: Me & I on September 1, 2010 Even if we concert photographers cannot influence the choreography, we can still use the remaining means, for example with the help of image composition, to create concert photos that are worth seeing. Concert photographers in particular have to be flexible. Here I photographed Adel Tawil from ich & ich. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70mm Nikkor, using a focal length of 70mm. 1/500 second, Blender 3.2, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Largely predetermined perspective(s)

Apart from a few exceptions, we concert photographers are not allowed to stand freely in front of or next to the stage. On the contrary: we are allocated certain areas (for example the stage pit) when we are accredited. It's good if we can move freely within the pit; however, this is often severely restricted so that we are forced to work under sub-optimal conditions and often in very confined spaces.

As most of the shots are therefore inevitably taken from the pit, which is usually in a recessed position directly in front of the stage, the "typical" concert photos look as if the photographers were lying on their stomachs on the ground in front of the musicians.

But perhaps this effect is intentional, because the musicians - even the smallest of them - always look much bigger and more "heroic" than they really are when photographed from below.

To ensure that the photographic quality does not suffer, you should take care that the distortion resulting from the low camera position (which is particularly noticeable when using wide-angle lenses) is not too noticeable. Professional photographers will of course immediately recognize the "stretching" of the musicians, who suddenly all seem to have long legs. However, it is crucial that "normal" viewers do not notice this effect - or at least that it does not appear unnatural or distracting.

Figure 3.4: Culcha Candela on August 20, 2011: Here, too, we photographers were standing right next to the stage, in the pit, which inevitably resulted in an extreme perspective from below for all photos (with the effect of emphasizing the lower extremities of the musicians, to the delight of the shoe sponsor). Nikon D3S with 4/24-120mm Nikkor, using a focal length of 24mm. 1/500 second, Blender 4.0, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

The low camera position from the trench also has other disadvantages: Often enough, speakers and elements of the stage technology block our view of the musician or musicians (as a whole). So only in exceptional cases will we get the feet and legs fully in the picture.

Figure 3.5: This photo clearly shows how extreme such a distortion can be, caused by the low camera position and the use of the wide-angle lens. The artist's left foot is shown oversized because it is very close to the camera. The upper body and head, on the other hand, which are tilted far back, appear unnaturally tiny in the photo. Dick Brave concert on August 26, 2012 in Bochum/Witten. Nikon D4 with 2.8/14-24 mm Nikkor, using a focal length of 14 mm. 1/200 second, Blender 2.8, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Because cables, speakers and other elements of stage technology are regularly located at the front of the stage, right in front of our noses, they inevitably appear again and again in concert photos (in the foreground and, unfortunately, disproportionately large when using a wide-angle lens). If you don't want to photograph these disturbing elements despite a poor view of the musicians, the only option for us concert photographers is to use longer focal length lenses. However, at least with musicians who are close to us on stage, only portraits in the narrower sense are possible.

Figure 3.6: If you take portraits at close range and from the (lower) pit, you have to accept that the nostrils of the musician (here: Jan Delay at the concert on August 20, 2010) will be particularly well (but unintentionally!) accentuated due to the perspective. If you want to avoid this, it is advisable not to photograph the musician standing directly in front of (or above) you at the edge of the stage, but to use telephoto or portrait telephoto lenses to photograph musicians standing further away (because then the angle is not so steep). This method may seem a little strange to viewers of the scene (when photographers take photos of the musicians standing further away from each other) - but it makes perfect sense from a photographic point of view! Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70mm Nikkor at a focal length of 56mm. 1/1250 second, Blender 3.5, ISO 5000.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

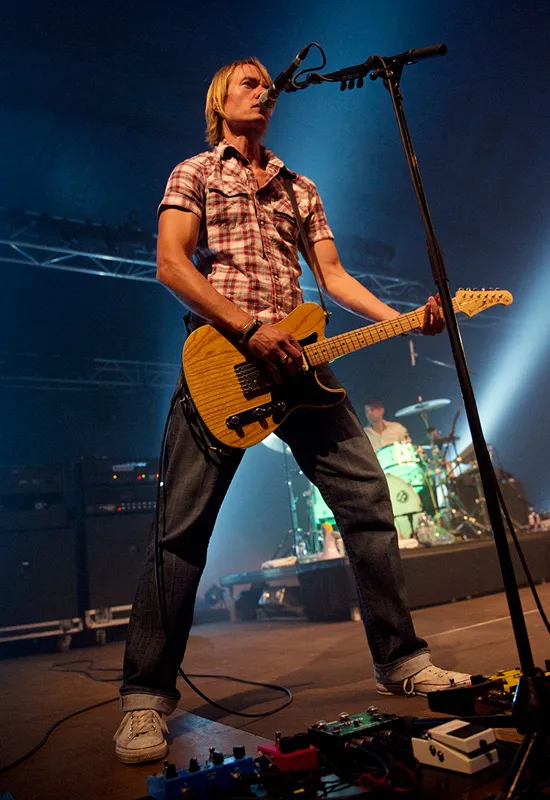

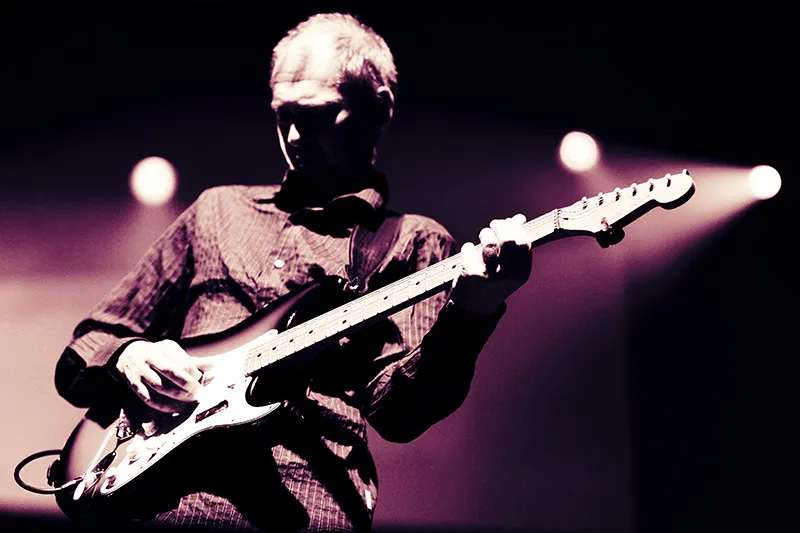

Figure 3.7: A "typical" concert photo: I gave the guitarist from the H-Blockx "long legs" in this photo (taken on August 31, 2010 at the ZFR in Bochum), which inevitably resulted from the short distance, the use of the wide angle and the tilting of the camera upwards (due to my lower camera position). The stage equipment can be seen nicely in the foreground, but in this case it wasn't so big that it would have blocked my view. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70 mm Nikkor, with 24 mm focal length used. 1/500 second, Blender 2.8, ISO 5000.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

It is even worse for us photographers when we are assigned a position by security that we are absolutely not allowed to leave. We are then forced to take all photos from this spot - regardless of whether it is suitable or not. A terrible idea for any creative photographer; but then there is nothing left to do but make the best of the (admittedly bad) situation.

However, in other areas of photography too, the conditions are not always ideal. You simply have to try to take special photos with the possibilities you have. As a professional photographer, I quickly learned to be flexible. You just can't despair in such cases, but have to try to use your skills despite all the adversities.

Figure 3.8: Even portraits of musicians, when taken during a live concert, usually show the typical perspective from below (with the unintentional view into the nostrils of the person depicted; in this case, however, I was lucky that the artist kept his head down, concentrating on his guitar playing).

I caught the guitarist from BAP at a concert on August 24, 2011. In order to separate the subject's head from the (often restless) background, I like to shoot with an almost open Blender. My favorite lens for this (with an ideal focal length for portraits when standing in the pit right next to the stage) is the 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. I usually stop down the lens slightly anyway (by about 1 f-stop; here it was 1+1/3 stops) to get better sharpness performance (compared to fully open aperture). Nikon D3S with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/250 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 1250.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Uninfluenceable, changing light situation

Another condition that makes photographing concerts always exciting (and also a bit random) is the changing light situation. Depending on the style of music and choreography, the lighting can sometimes change extremely quickly.

It is not uncommon for the light to change in the short space of time between when the photographer decides to press the shutter release button and the actual exposure. Such fractions of a second can result in a shot that is completely different from the intended one because the light has already changed again.

Figure 3.9: Wir sind Helden on August 25, 2011: These two shots were taken within a second of each other - and yet the lighting turned out completely different. So concert photographers have to react quickly, and sometimes a good dose of luck also plays a role, because only very rarely can the light changes (time and type of lighting) be predicted. Nikon D3S with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/320 second, Blender 4, ISO 2000.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

The above makes it clear why concert photographers prefer cameras with the shortest possible shutter lag. (The shutter release delay of the Nikon D4 I use, for example, is 42 milliseconds, i.e. 0.042 seconds).

You have to realize that the effective lighting that makes concert photos so exciting consists primarily of backlighting! In combination with the fog, the effective light from the background of the stage produces the extraordinary lighting effects worth seeing.

The fog is necessary because the light alone would not be visible. If there were no fog or dust particles in the air, you would only see the lamps - but not the photogenic rays of light.

Figure 3.10: RUNRIG at their concert on August 29, 2012 in Bochum. Due to dust and fog particles in the air, the effective light beams of the spotlights are clearly visible. If, on the other hand, you could only see the spotlights (i.e. the origin of the light beams), the lighting would be relatively uninteresting.

That's why the fog machine is an essential part of the lightshow! Just a tenth of a second earlier, guitarist Donnie Munro was still sufficiently brightly illuminated from the front by a spotlight; however, the moment I pressed the shutter release of my D4, it was already off again - and as with a silhouette, only the silhouette of the singer could be seen. However, I still liked this photo because of the colorful, effective lighting, so I didn't sort it out. Nikon D4 with 2.8/14-24 mm Nikkor, focal length 19 mm. 1/80 second, Blender 2.8, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Note

Even though backlighting always carries the risk of light rays falling directly into the lens (the use of a lens hood is therefore strongly recommended), the problems with exposure mainly arise from the speed at which the light show changes. Even difficult lighting situations can be solved photographically, resulting in good photos. However, this is hardly possible if the lighting situation changes quickly and constantly. Then there is no time left to think; the photographer has to act intuitively, so that successful photos are always a bit dependent on chance (luck)!

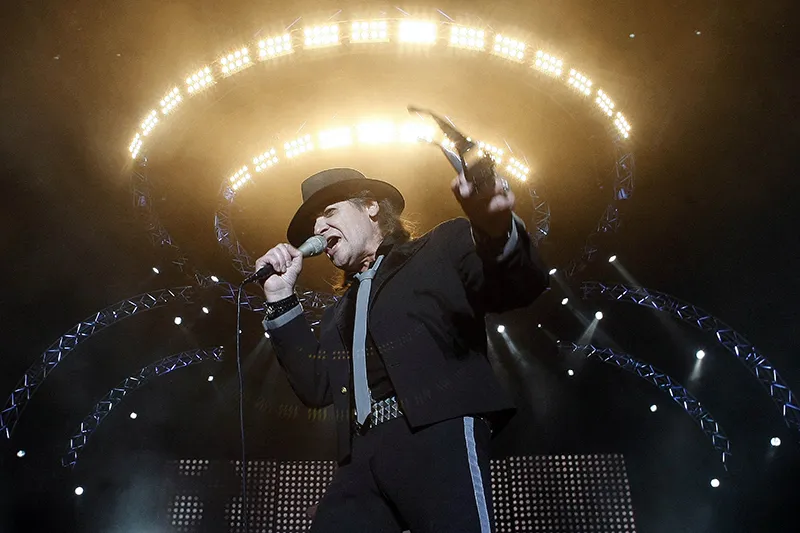

Figure 3.11: Here, "Panic Rocker" Udo Lindenberg was perfectly captured at the concert in Berlin on October 15, 2008 - with a "halo". As well as being able to react quickly to press the shutter release at the right moment, you also need a good dose of luck, because it is common knowledge among concert photographers that lighting situations generally change faster than you can think. In this situation, the photographer's low vantage point was exceptionally advantageous, as this "halo" effect would not have come across so well from further away or from a higher vantage point.

(Photo © 2008: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

Of course, it would be nice if the lighting of the musicians and the stage were coordinated with the photographers - but these are pipe dreams that are unfortunately unrealistic (except perhaps for advertising photos commissioned by the band). So we concert photographers are passively condemned to accept the lightshow as others (lighting technicians and choreographers) have devised it. Anyone who has difficulties with rapidly changing lighting is advised to start practicing at concerts where there is less "unrest" from a lighting point of view. At classical concerts, chansons and pop music, etc., few and slow light changes are to be expected, as well as at concerts in small music pubs, where the financial means for fancy lighting technology are lacking.

Figure 3.12: Wir sind Helden on August 25, 2011 at the Zeltfestival Ruhr in Bochum/Witten at the Kemnader Stausee. At this concert, all the photographers cursed loudly, because with the strange "kitchen lamps", which cast bright white light from above onto the performers around singer and front woman Judith Holofernes, it was almost impossible to achieve decent portraits of the individual band members. The resulting contrasts were too strong: a very unfavorable light (even for the musicians!)! I used the fisheye to take an overview shot of the whole stage - standing right next to the stage in the pit. All the things that are often - and also here - on stage are clearly visible in this photo: Water bottles for the band, extension cables, "cheat sheets" with the song program, distribution sockets, speakers and other stage equipment. Nikon D3S with 2.8/10.5 mm Nikkor. 1/200 second, Blender 4, ISO 2000.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Color cast due to the stage lighting

Color casts in the color of the dominant spotlight(s) are actually a desired effect in concert photos. Imagine if only white light was used at a concert: The photo results would be boring. Colored light therefore plays a not insignificant role in the mood at parties and concerts, and colored light is also far more interesting from a photographic point of view - at least in this context.

Figure 3.13: Celine Dion at a concert in Berlin on June 12, 2008. With natural-looking white light, concert photos look much less spectacular - even when a world star is on stage. (Photo © 2008: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

Sometimes, however, the resulting color cast - especially on the musicians' faces - can be too strong and have an unattractive or disturbing effect on the viewer. Remember: we cannot (must not!) simply "flash away" a color cast.

It is interesting to see how differently the colors appear:

- green color cast: usually looks unflattering because the musician makes such a "sickly" impression (yellow has a similar effect).

- blue color cast: blue looks cool; sometimes the skin looks a little pale when illuminated in this way.

- Red color cast: looks dynamic to aggressive; goes well with hard rock and heavy metal; with a strong red cast, it is difficult to weaken the effect by means of color saturation because the skin then fades.

Figure 3.14: Sunrise Avenue on August 27, 2012: In this photo, I filtered out the green cast a little in the subsequent image processing in Photoshop so that it is no longer too disturbing. Otherwise, green light is similar to yellow light - rather unsuitable for direct lighting of the individual musicians. It makes the skin look sickly very quickly. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/800 second, Blender 2.5, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Figure 3.15: Sunrise Avenue on August 27, 2012: Here, too, I used Photoshop to filter out the blue cast with the help of color saturation so that the artist's skin tones don't look quite so unnatural and pale. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/1000 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Figure 3.16: Tim Bendzko on August 24, 2012 in Bochum. I was only able to reduce the red cast slightly; I couldn't get rid of it completely, because if you reduce the color saturation of red, the skin looks pale very quickly, because the skin tones consist largely of red. Nikon D4 with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/200 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 2,000.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Conclusion on the subject

Color casts in concert photos are intentional; they make the photos spectacular. However, the color cast can also be distracting in photos of people, especially if it distorts the artist's face. One method to reduce this effect is to reduce the color saturation of the corresponding color in the image processing. Care must be taken here that this is only done very slightly, as too much reduction will quickly make the face look pale and unnatural.

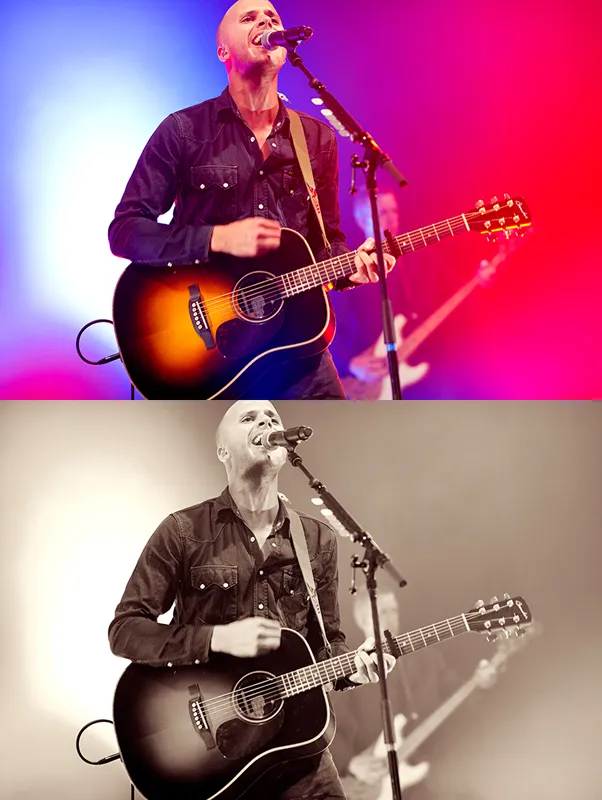

Figure 3.17: Another way to eliminate an unwanted color cast in the artist's face is to convert the entire photo to black and white (or sepia). This method may seem a little "brutal" at first glance, but black and white photos are still "in".

You just have to see how the photo in question looks in black and white, because not all of them look just as good (or even better) when you remove the colors. The photo shows Milow at a concert on September 1, 2011. Nikon D3S with 1.4/85 mm Nikkor. 1/160 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 1250.

(Photo © 2011: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

No Flash

Another special feature of concert photography is the ban on using your own lighting. Of course, this refers in particular to the photographer's own system flash unit ("clip-on flash"). There are several reasons for this:

- The use of the photographer's own lighting (such as the system flash) would change the lighting mood (which has, after all, been approved by the musicians): The lightshow would then no longer really come into its own in the photos. Of course, you can also use the system flash discreetly in the foreground, just to brighten up the artist, so to speak. However, musicians and their management cannot assume that all photographers would use their light so skillfully.

- When you are on stage and perhaps a little nervous about the performance, the flurry of flash that would occur if the photographers were allowed to use their own system flash units can be very distracting and distracting for the musicians.

- If the musicians were flashed directly in the eyes with a powerful flash, they could be dazzled and no longer be able to properly recognize important details, such as program sequences pasted to the stage floor, which could result in uncertainty or even the disruption (interruption) of the concert.

- Security could also feel disturbed, as one of their tasks is to detect disturbances in the audience as quickly as possible, pull people who have fainted out of the crowd and prevent panic. This becomes more difficult when there is a constant flurry of flashbulbs coming from the press pit.

- And last but not least, the audience could also feel disturbed. After all, the constant flashing from the press pit would unnecessarily distract from the actual show (which takes place on stage from the audience's point of view).

Figure 3.18: In this case, the discreet use of a flash would also have ensured that the blue tint in Bushido 's face (here at his Berlin concert on September 28, 2006) would have been softened and the face would have stood out better. If the system flash is skillfully used with reduced power, the lighting mood of the concert photos is not destroyed and the disturbance of the artists (through glare) is then only minimal and negligible. But the industry does not want to rely on the fact that only experienced photographers take concert photos; there are always enough people who get an accreditation who do not use their photo equipment skillfully and would really disturb the musicians with a storm of flashbulbs.

(Photo © 2006: DAVIDS/Sven Darmer - www.svendarmer.de)

Conclusion

Even if other solutions (e.g. only discreet "fill-flash") were theoretically possible, it is unlikely that concert photographers will be allowed to bring and use their own light sources (mainly system flashes) at events in the future due to practicality. So we have no choice but to make the best of the respective (lighting) situation. As already emphasized: Photographers have to be flexible if they want to be successful on the market.

Figure 3.19: Runrig on August 29, 2012: If I had been allowed to, I would have brightened up the guitarist's face. Since that wasn't possible, I simply focused on the guitar and even increased the contrasts when editing the image later in Photoshop. Nikon D4 with 1.8/85 mm Nikkor. 1/500 second, Blender 2.2, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Three songs?

As a commercial photographer, I turn down jobs that are scheduled by the client for less than four hours. Firstly, because I can't be creative enough under stress. And secondly, because only photographing variations guarantees that exceptional photos will result. But I need enough time for that!

There are certainly other reasons why four hours of photography should be planned as a minimum (for example, the impossibility of planning everything perfectly down to the last detail). But the two reasons mentioned above are enough to make it clear that exceptional photos are not created by "magic", but by hard (diligent) work.

In this respect, I was quite shocked during my first assignments as a concert photographer that we photographers had to work under such adverse conditions. After all, I naively thought at the time, the artists (and also their management and the concert organizers) should have an interest in the best possible photos being taken at the concerts. Only first-class photos - so my thinking at the time - are also an advertisement for the respective event.

I now know that we "visually-driven" photographers have different priorities and evaluate things differently to the musicians (and everyone who works with them): From their point of view, the acoustics may be much more important than artistically and photographically sophisticated photos. It's obvious that we photographers see things differently.

What's more, at some point, some superstars (and the stars in the pop sky, including Britney Spears, for example) started to impose more and more rules on photographers, presumably for reasons of vanity. For example, that photos could only be taken from a certain place within the pit in order to show only the "chocolate side" of the artist.

And at some point, this also included limiting photography permission to the first three songs of each performance. This was presumably an attempt to present the artists fresh and without beads of sweat on their foreheads (and above all without sweat stains on the T-shirt under their armpits). (After all, for some musicians the image is (often) more important than the music itself).

Another reason for limiting the duration of photography to just the (usually first) three songs may be to prevent photographers from being accredited in order to attend the concert for free. (In other words, if private interests are the reason for being accredited as a photographer).

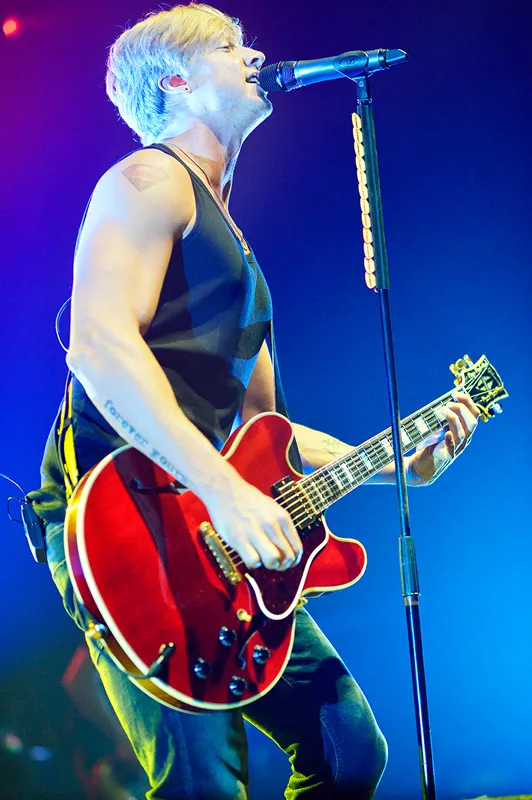

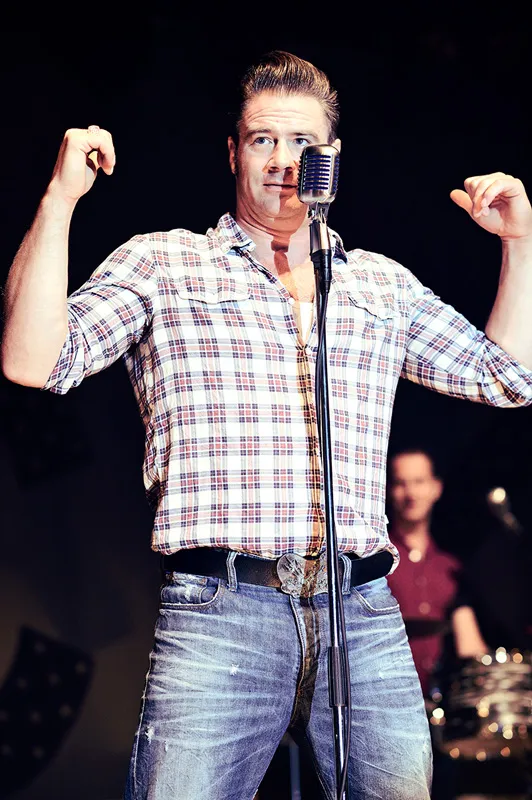

Figure 3.20: When you only have three songs to photograph, you learn to work quickly and efficiently. Nevertheless, it often happens that the best scenes are not photographed at all because the artists also need a bit of time to warm up. With Dick Brave (aka Sasha), here on August 26, 2012 with his band The Backbeats at the Zeltfestival Ruhr, the show starts right from the first song. For the photographers, this means: rockabilly macho poses guaranteed right from the start! Nikon D4 with 1.8/85 mm Nikkor. 1/320 second, Blender 2.5, ISO 2500.

(Photo © 2012: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)

Final conclusion

If you only have the duration of three songs to photograph during a concert, this is a severe limitation of photographic possibilities - but of course also a great challenge! Ultimately, concert photography has become what it is today mainly because of this restriction: photographers are already in a state of stage fright beforehand. They nervously check the camera settings for the tenth time beforehand. The inserted memory card is formatted for the fourth time and the availability of spare memory cards in the photo backpack is checked for the fifth time - even if, due to the short duration of the shoot, no photographer is ever embarrassed by having to replace the (fully-filled) memory card. (The time is too short to (sensibly) fill an 8 or 16 gigabyte memory card with shots).

This stage or hunting fever is simply part of concert photography. Photographers are aware of the limited time they are given and are anxious as to whether they will manage to bring home enough successful photos. In no other field of photography have I seen photographers checking their photos (still in the camera, on the display) with such excitement after the event; nowhere is the joy over successful results expressed as loudly as in concert photography and nowhere is the fist raised so triumphantly when looking at good results if the photographer is satisfied with himself and the photos.

Figure 3.21: ich & ich on September 1, 2010: frontman Adel Tawil (now mainly a solo artist) puts on a great one-man show for the first three songs (the second "ich", Annett Humpe, does not perform at the concerts). Nevertheless, the photographers would have liked to stay even longer - but there was hardly any grumbling when the security led the photographers out of the pit again after just three songs. Nikon D3S with 2.8/24-70 mm Nikkor, with 24 mm focal length used. 1/1250 second, Blender 3.2, ISO 3200.

(Photo © 2010: Jens Brüggemann, www.jensbrueggemann.de)